Ray Carter, a Labour MP for Birmingham – home to thousands of automotive workers – pressed the issue in parliament in January 1975.

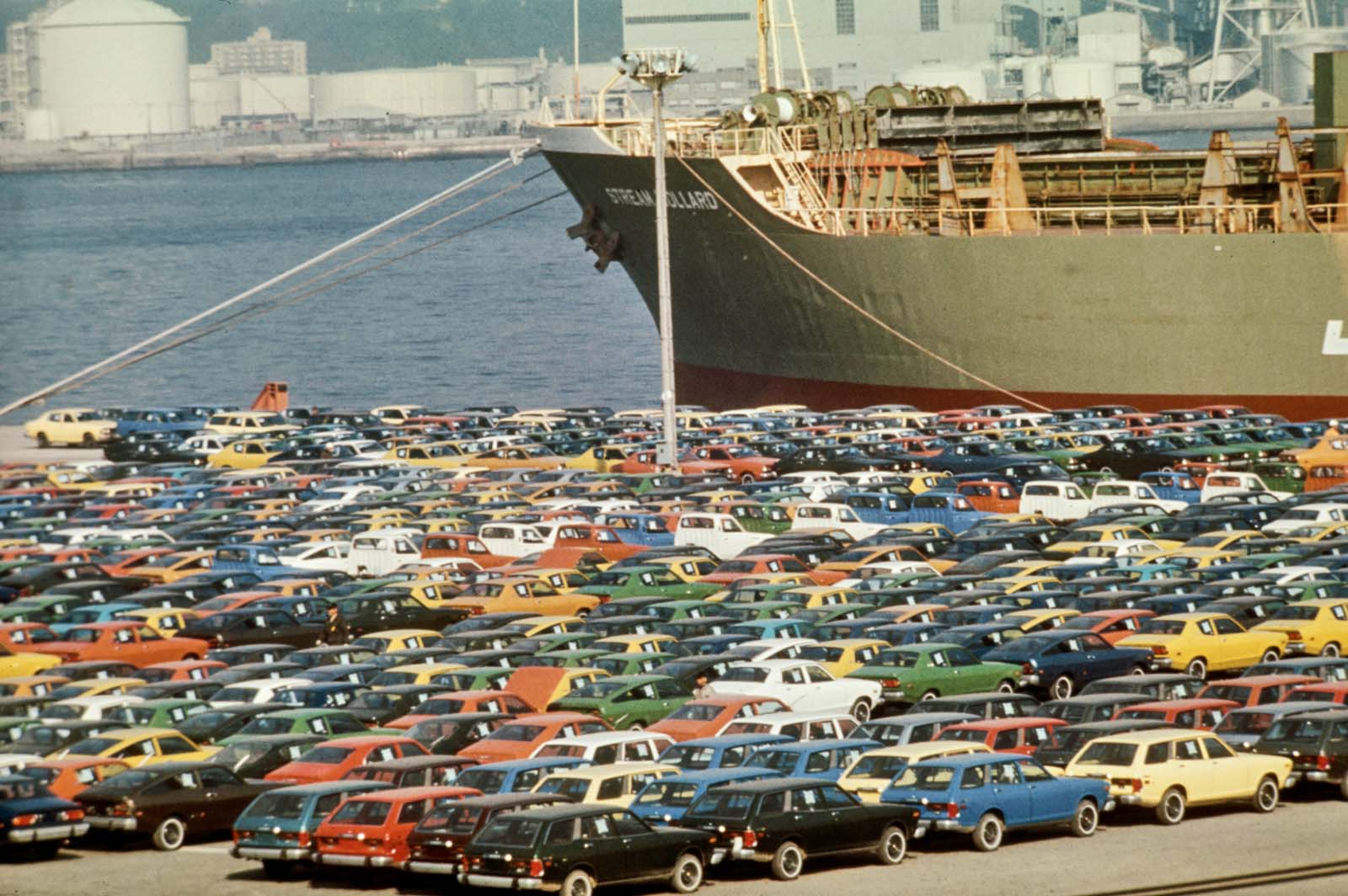

“My call is not for a ban on the importation of Japanese cars but for the British industry to obtain a basis of fair trading in which British manufacturers can export to Japan in the same free and unhindered manner that Japanese manufacturers can export to Britain,” he said, pointing out that Japan was exporting some 62 times more cars than it was importing.

“Japanese manufacturers and dealers have been prepared to cut corners to gain the depth of penetration they now have into the British market and are currently offering cars at rates of interest on [HP] approximately one-third of what would have to be paid to buy a British car. That is felt by British manufacturers to be an unfair trading practice.”

The minister for trade’s response? “I sympathise with the fears which prompt such demands, but I do not think that it would be right for the [Labour] government to accept the logic which seeks to justify them.”

But that December, the SMMT met with its Japanese counterpart to make “its usual complaint” – and JAMA promised “the level of sales achieved in the latter part of 1975 would be continued for at least the first three months of 1976”, keeping its members’ share at about 10%. Why? We assume primarily because the SMMT threatened legal action under the Customs Duties (Dumping and Subsidies) Act 1969.

By April, the two trade bodies were arguing. The SMMT alleged Japanese firms weren’t honouring their ‘voluntary agreement’ – which JAMA vehemently denied, adding: “It appears the restraint expected of [us] simply means the substitution of [our] cars by other foreign cars.”